A First Dive Into System Design

How to Operationalize and Scale a Web App

What does it take to generate and insert ten million data points into a database efficiently? What strategies can we implement to handle thousands of user requests per second on our service?

These were the burning questions my team and I faced in the final phase of our 13-week bootcamp. Up until then, our primary focus had been on the front end. Question about a bug? Drop a console.log(). State not rendering? Consult the dev tool GUI. Checking underneath the hood and optimizing server capabilities? Now that’s a different story. Our focus had shifted towards areas with less visibility and we had to adjust our strategies accordingly. But fret not! After all, decrypting the magic of the servers and databases is essential to becoming a well-rounded developer. With that in mind, we dove headfirst into the mysteriously exciting world of system design.

Creating the 10,000,000

For background, our team was given a functional legacy codebase to perform queries off of. The problem was that this existing database only housed 100 records. Each of us had to develop our own techniques to increase that figure to 10,000,000. Scary number isn’t it? As it turns out, ten million records is not much to brag about when it comes to large scale production sites (think facebook.com).

To hit this mark, I first needed a function that would generate unique sets of items. Since the existing codebase UI copied a Nike product page, this meant generating shoe artifacts with fresh new information every time. With help from several helper functions, I created a random shoe generator that encapsulated data points such as shoe name, price, size - the kind of details that come to mind when you think about a Nike shoe.

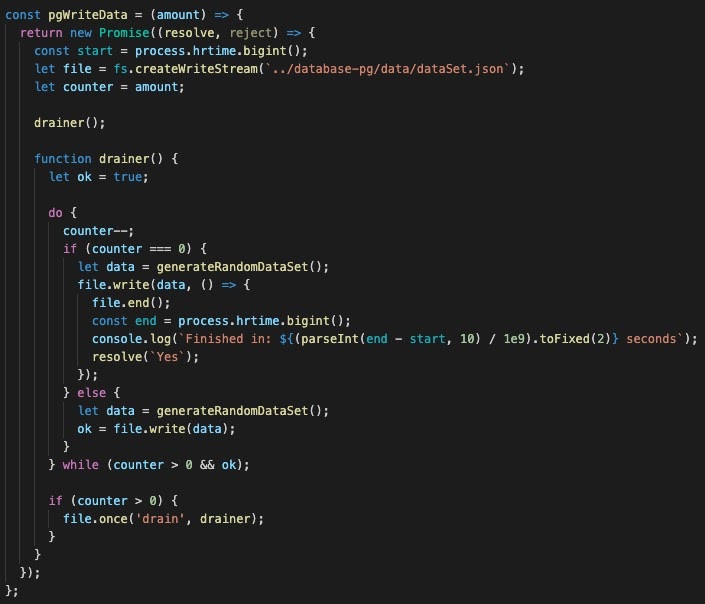

With a generator function up and running, I ran into a new challenge. Turns out writing data into a JSON file temporarily took up a sizable chunk of RAM space. How was I supposed to run this function ten million times without overloading my machine? After some digging, I found the answer in fs.createWriteStream() and a drainer() function.

According to documentation, everytime we call the write() method we write data to an internal buffer. Once this buffer reaches its capacity (or exceeds its highWaterMark property), the drain event fires to prevent more data from being written while simultaneously “flushing” the previously occupied memory. Doing so prevents high memory bottlenecks and crashes.

And just like that, I had successfully occupied my JSON file with 10-million unique nike shoe objects in a little under 5 minutes.*

*Make sure to add this aggressively large JSON file to your gitignore before pushing your repo!

Choosing a Database

Next, my job was to copy these 10-million records over into a database of choice. The legacy server had used MongoDB, but switching over to a relational (SQL) database such as PostgreSQL was also an option. To identify which better suited our needs, I had to weigh some pros and cons and benchmark the two.

Traditionally speaking, MongoDB and other document databases excel at working with formats such as JSON data. However, recently PostgreSQL has also begun offering enhanced JSON storage capabilities. Some online sources will say that PostgreSQL offers transactional integrity and data optimization features at the cost of speed and performance. But at the same time, a test in 2014 showed PostgreSQL beating out MongoDB in categories such as data ingestion, selection, and inserts by large margins. On the other hand, MongoDB proved superior in updating individual fields whereas PostgreSQL required one to extract the whole document and rewrite it back after changes were made.

Considering that my service only required searching an individual product given an ID, I decided PostgreSQL would be my best bet. Its JSONB representation automatically assigned an auto-incrementing ID to each item. This in conjunction with PostgreSQL’s index-only scan meant that queries would only check over the auto-incrementing ID and save time by ignoring the rest of the table’s data (also known as the “heap”).

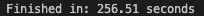

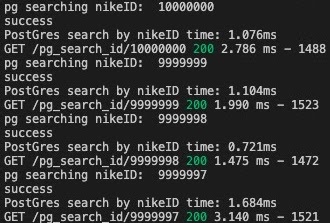

Just to be sure, I seeded both databases and benchmarked individual query time against each other. With a bit of performance tuning and optimization, I was able to achieve the following results:

MongoDB:

PostgreSQL:

Sure enough, PostgreSQL saw an all-around faster querying speed.

Stress Testing on a Local Machine

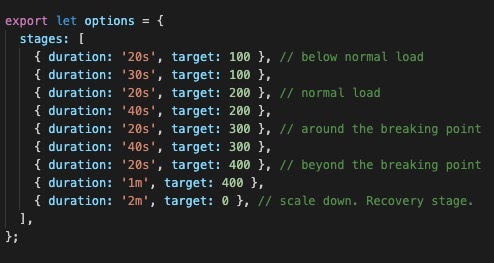

Now it was time to simulate virtual users making multiple queries on our local machine. I opted to use k6 as it mimicked traffic spikes by rapidly increasing and decreasing the load in stages.

What this test is saying is that over the duration of X seconds, slowly ramp up to X amount of virtual users making requests. At our breaking point, we aimed to ramp up to 300 requests over 20 seconds. While certainly not a lot to handle, it was interesting to see how it would affect the speed of my laptop’s response time (otherwise known as latency).

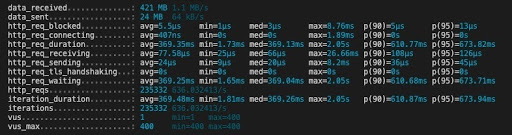

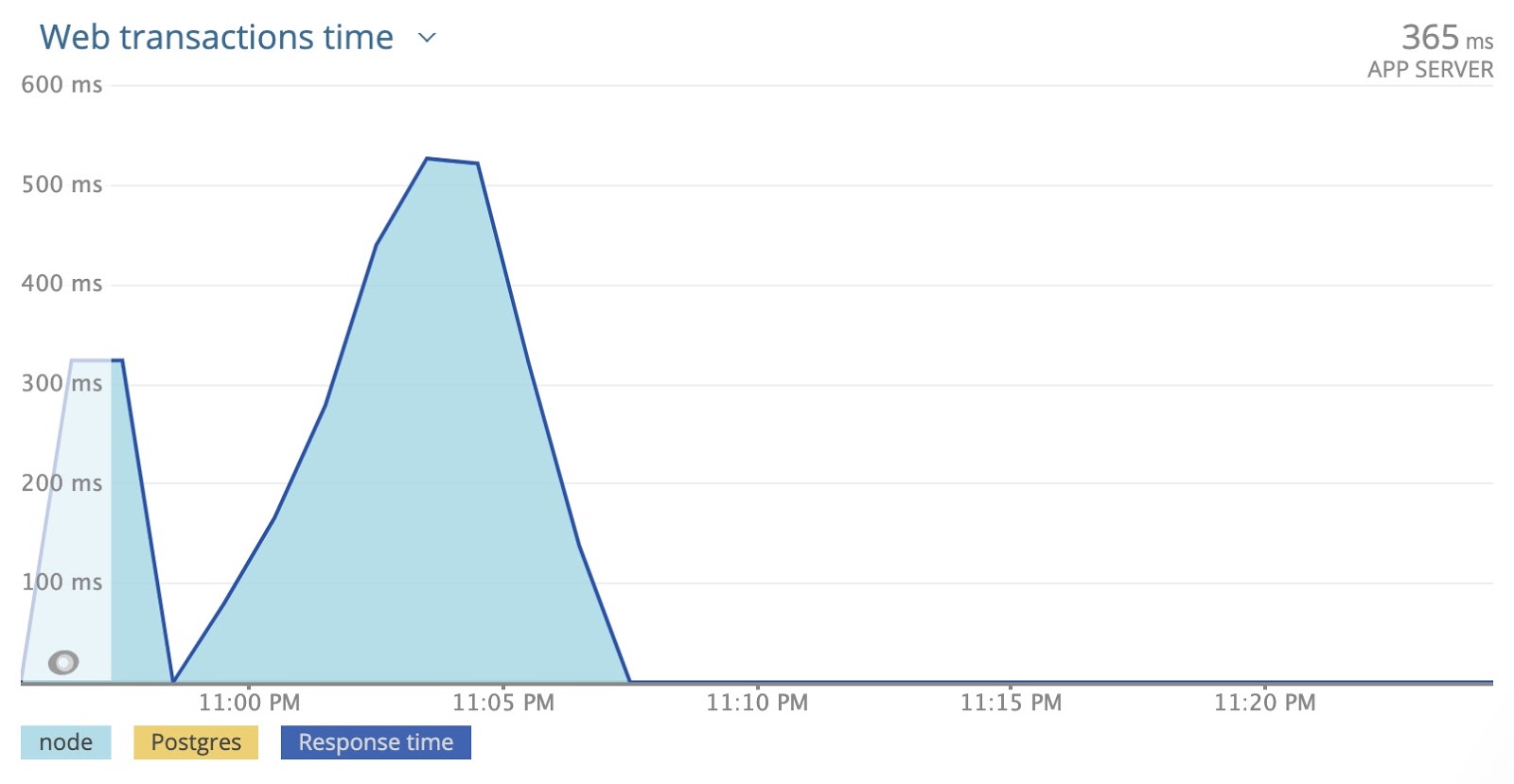

While the above data may seem confusing at first, pay close attention to the line "http_req_waiting". This represents the time waiting for a response from the remote host. New Relic does a clearer job of depicting the latency.

On average, a request takes 365 ms to process. According to k6, at the peak of 300 virtual users, a request could take as long as two whole seconds! Compared to individual query times of around 1-2 ms, this was certainly a loss in performance. To do better, we needed to scale.

Deploying on an EC2 Instance

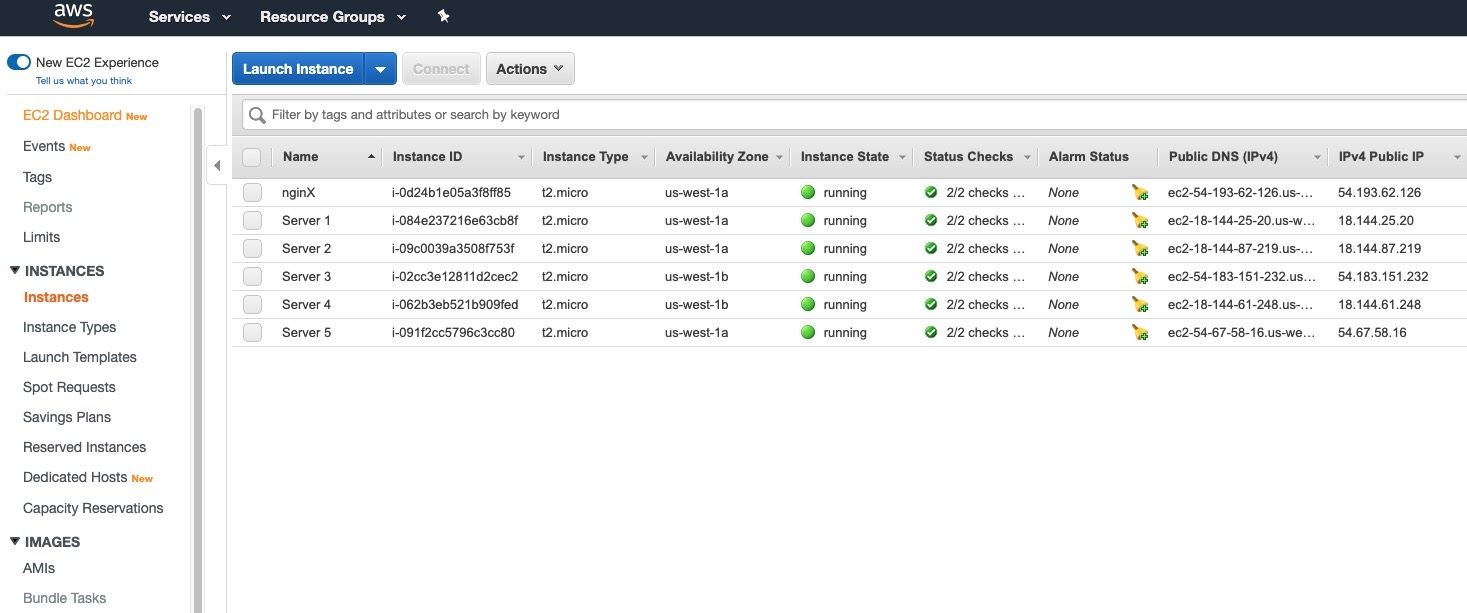

Two commonly known techniques to handle more traffic are vertical scaling and horizontal scaling. To put it as simply as possible, vertical scaling works by adding more power (CPU, RAM) to an existing machine. Imagine a computer that grows to handle more stress by getting taller and taller (i.e. growing vertically). On the other hand, horizontal scaling means the computer size stays the same but we lessen the individual load by adding more same-sized computers to the mix. Imagine a net made up of computers that grows horizontally to distribute the traffic load evenly. For learning purposes, we decided to see what strategies we could employ by horizontally scaling using AWS T2 micro instances.

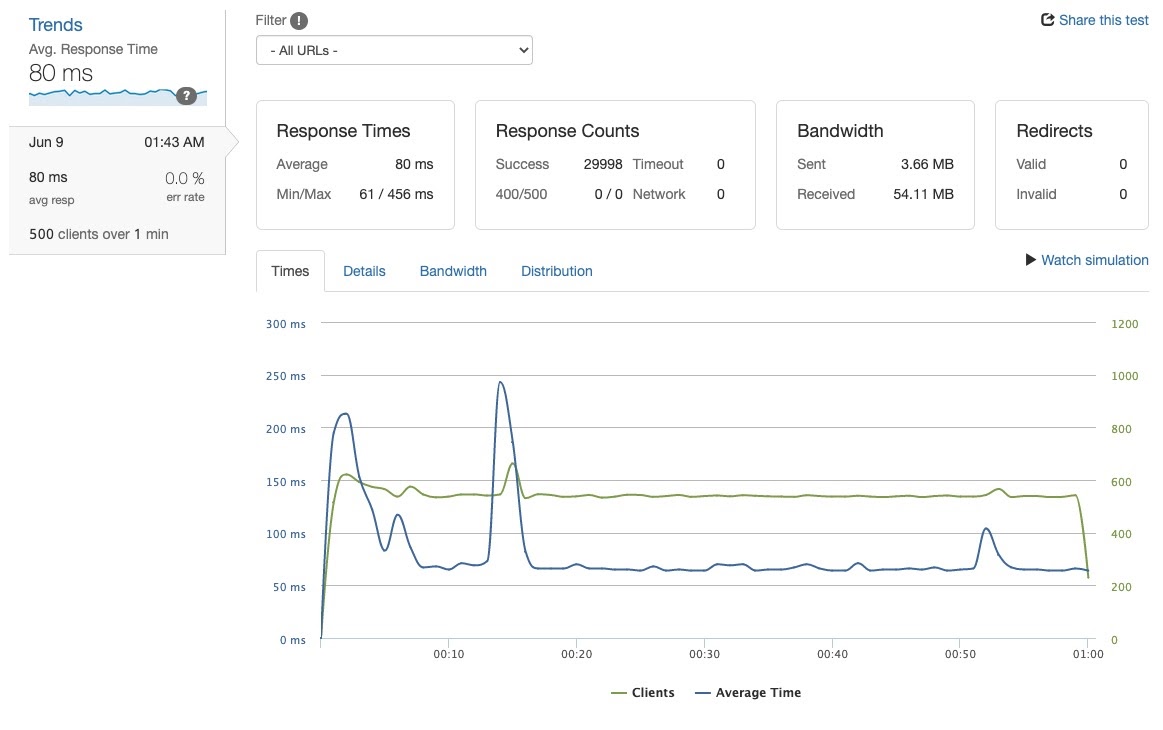

Starting off with a single instance, I simulated 500 responses per second (RPS) over 1 minute using Loader.io.

80 ms response time on average at a 0% error rate. Not bad; certainly better than our local machine. Now how about 1000 RPS?

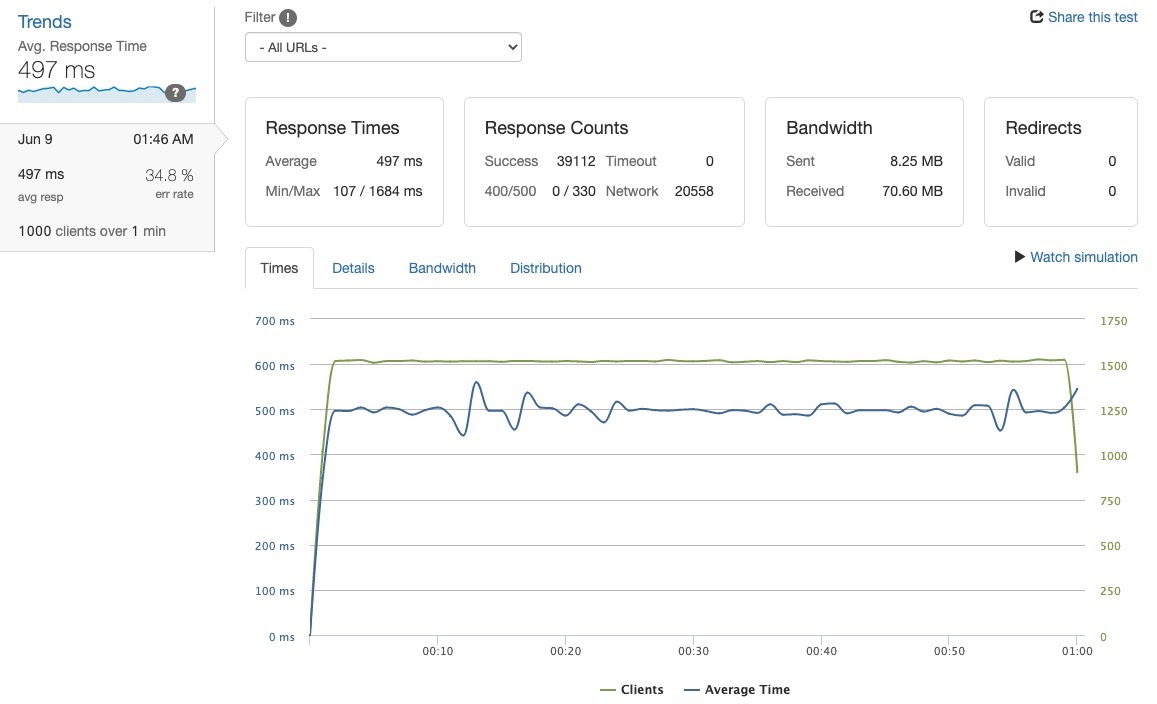

The RPS climbed dramatically and the error rate shot up to 34.8%. Certainly not the user experience we would want to see on a production level site. Let’s see how we improved those numbers.

Load Balancing and Horizontal Scaling

We briefly discussed the concept of horizontal scaling earlier, but how is it done? Turns out there were many ways of distributing the traffic over multiple server instances (also known as load balancing). After some research, I settled on using a popular, open-source software known as NGINX.

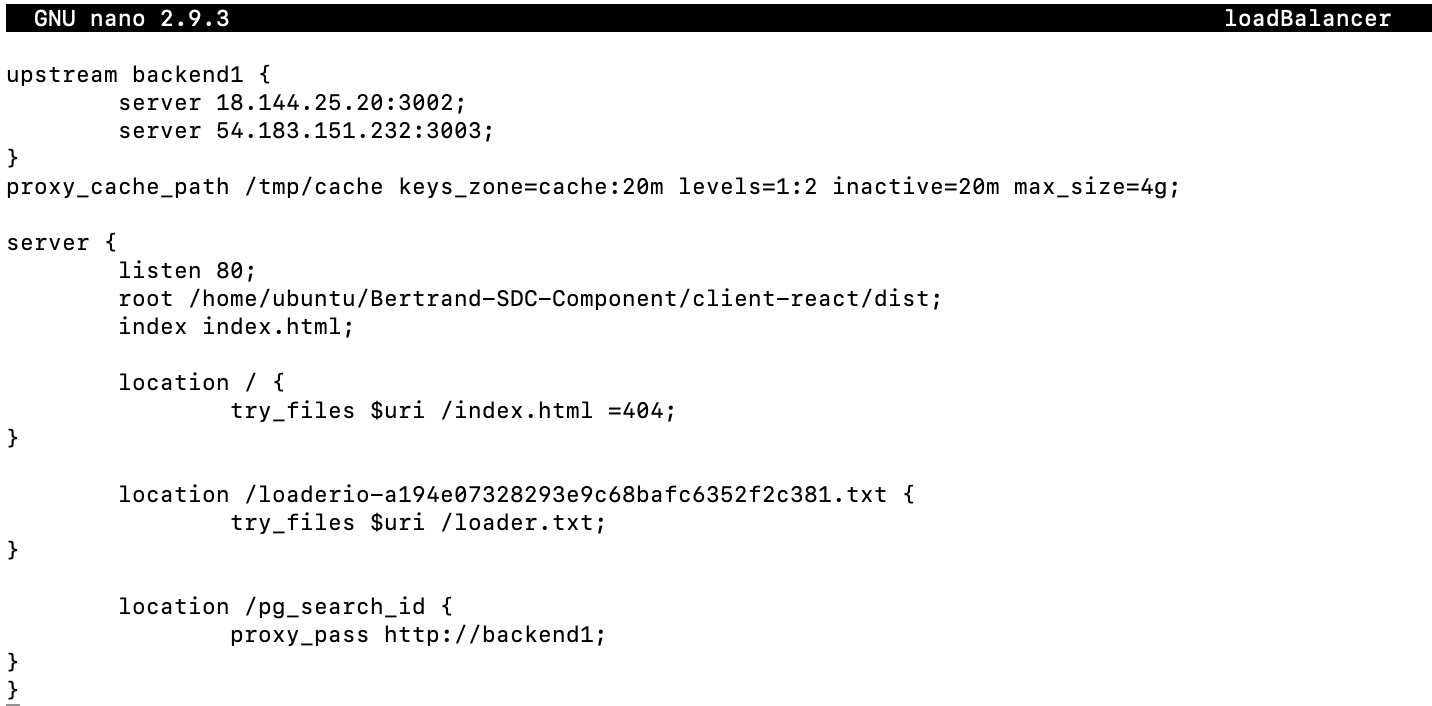

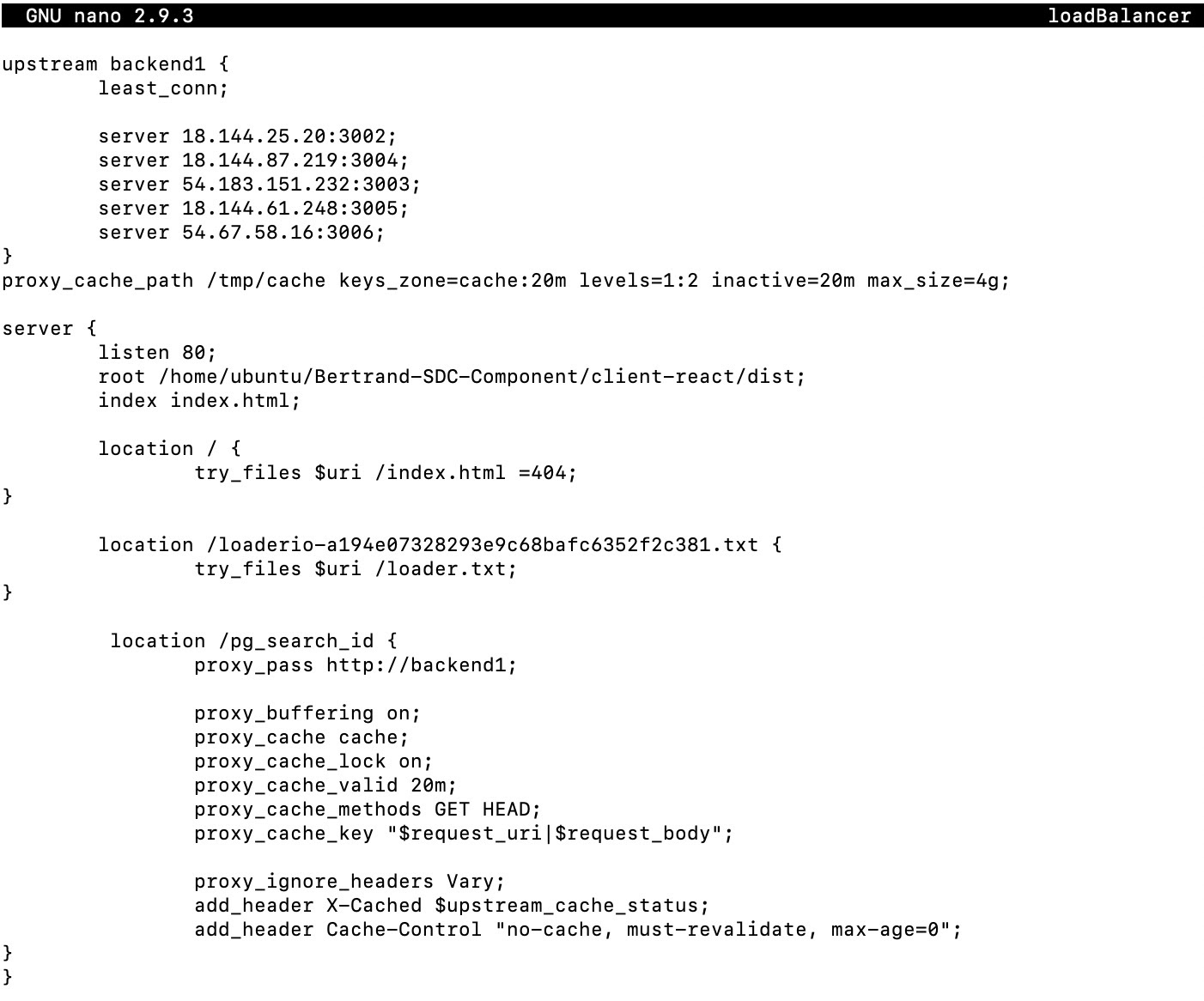

While there was a brief learning curve, the setup went smoothly given clear documentation on what to do. After launching a second EC2 instance and a separate NGINX instance, I linked the three together in the configuration file like so:

Now requests being sent to the NGINX server’s endpoint would be distributed between both servers, thus lessening the strain on each individual one. It’s important to note that only one database is being shared between the two servers.

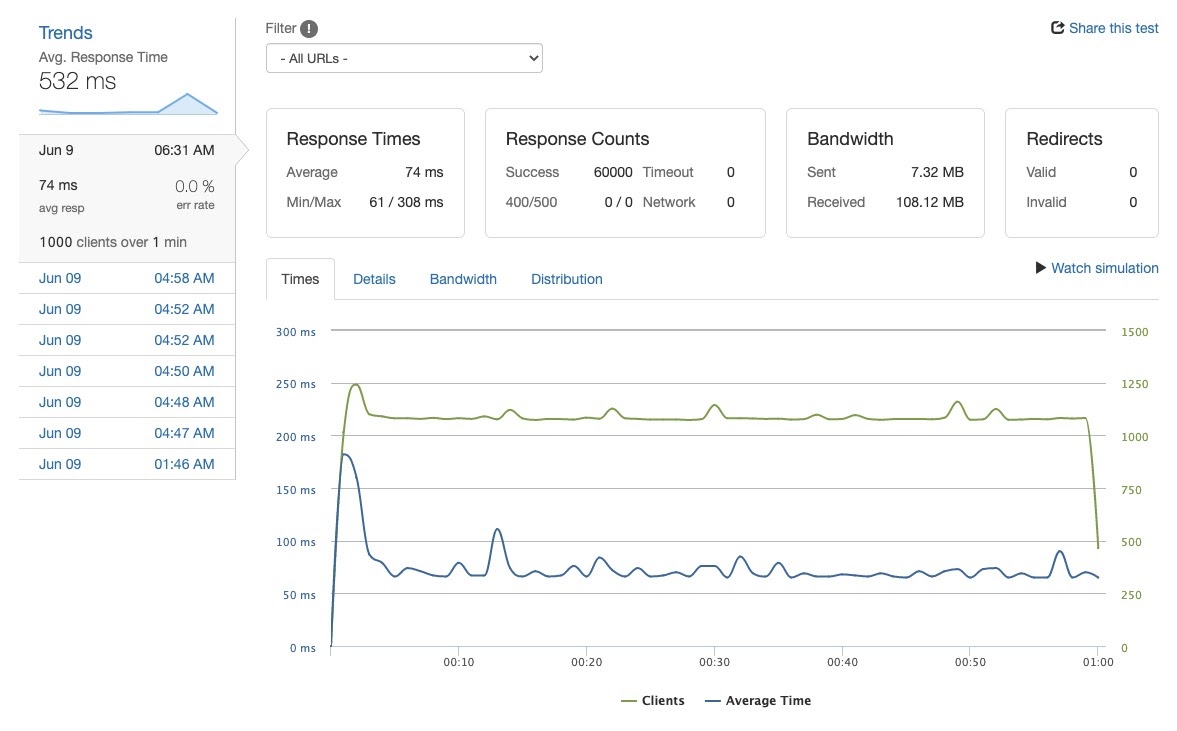

With two servers and a functioning load balancer, I booted up Loader.io again:

Where 1000 RPS had previously drawn an error rate of 34.8% and a latency of almost 500 ms, we now had a 0% error rate at a latency of 74 ms. Woot!

Let’s see how far we can take this…

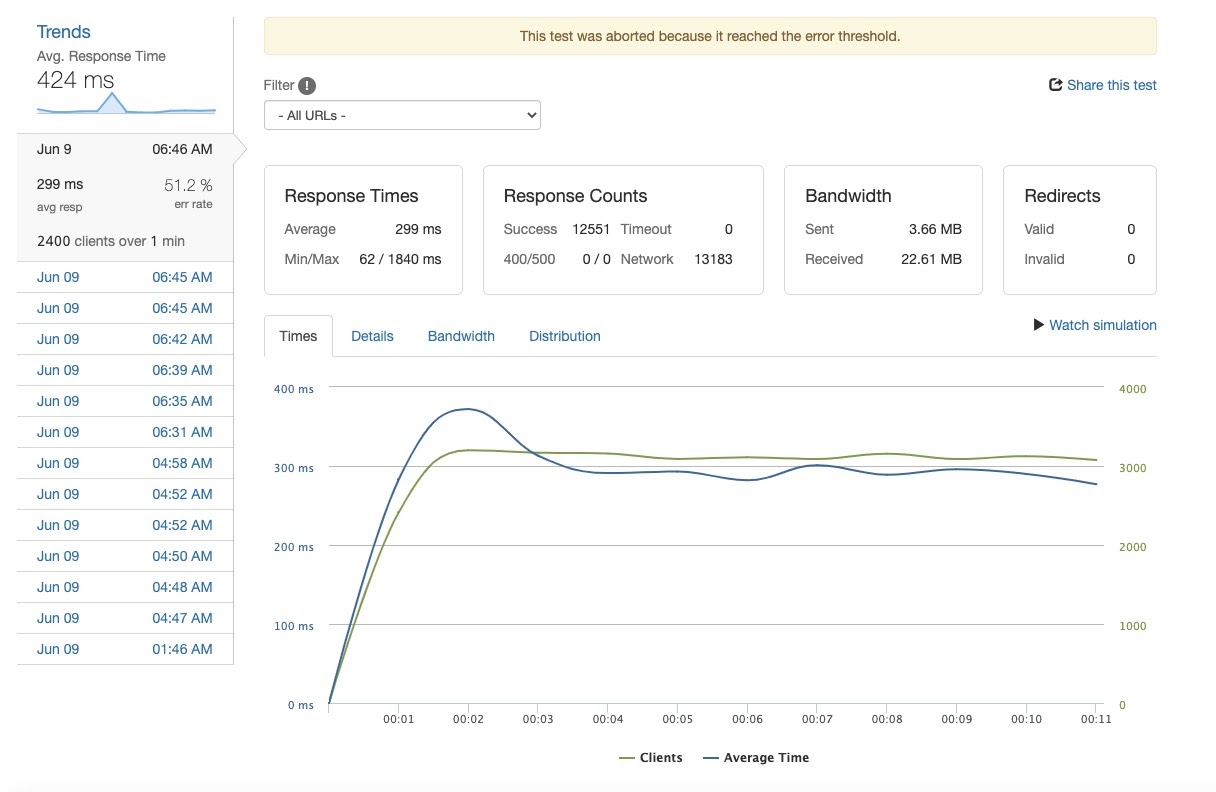

We made it all the way to 2400 RPS before reaching an error threshold of 50%. An incredible feat compared to a single running server. However, error rates started increasing at as little as 1500 RPS. For a practical user experience, we could not allow for errors like that. We had to do even better.

I scaled up to five separate instances and recorded the results each step of the way.

Along the way I noticed a few things. As shown above, the difference between one server and two was night and day. However returns certainly diminished by server four and five.

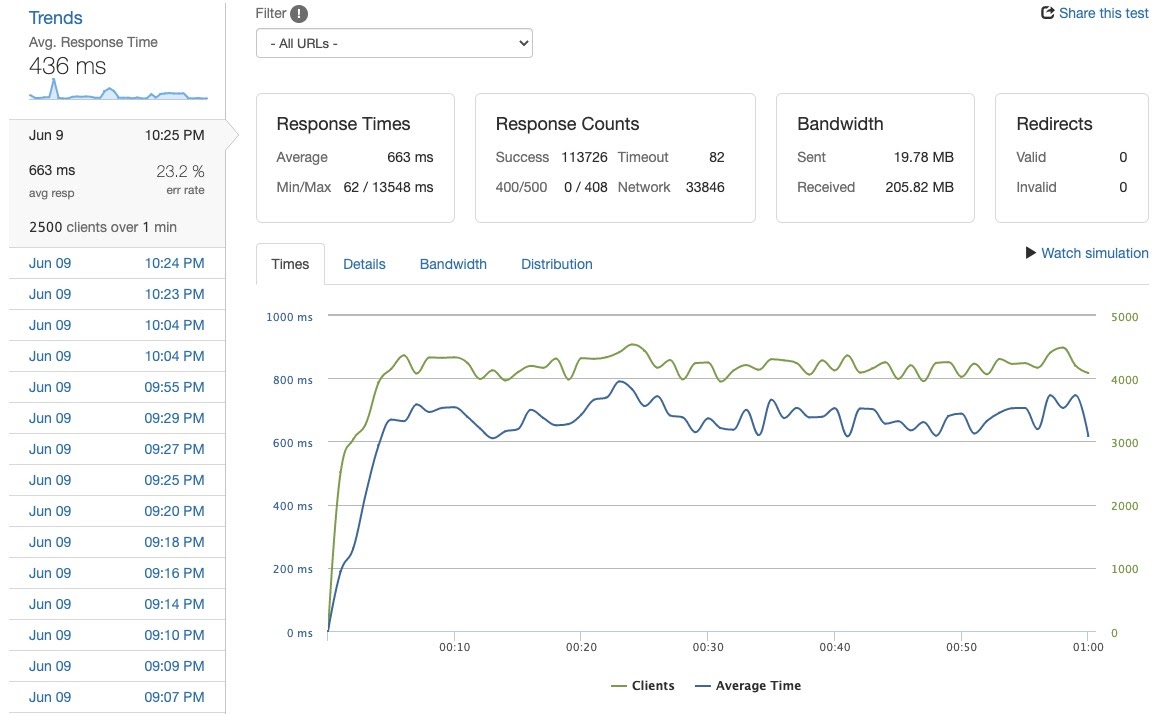

2500 RPS at server 4:

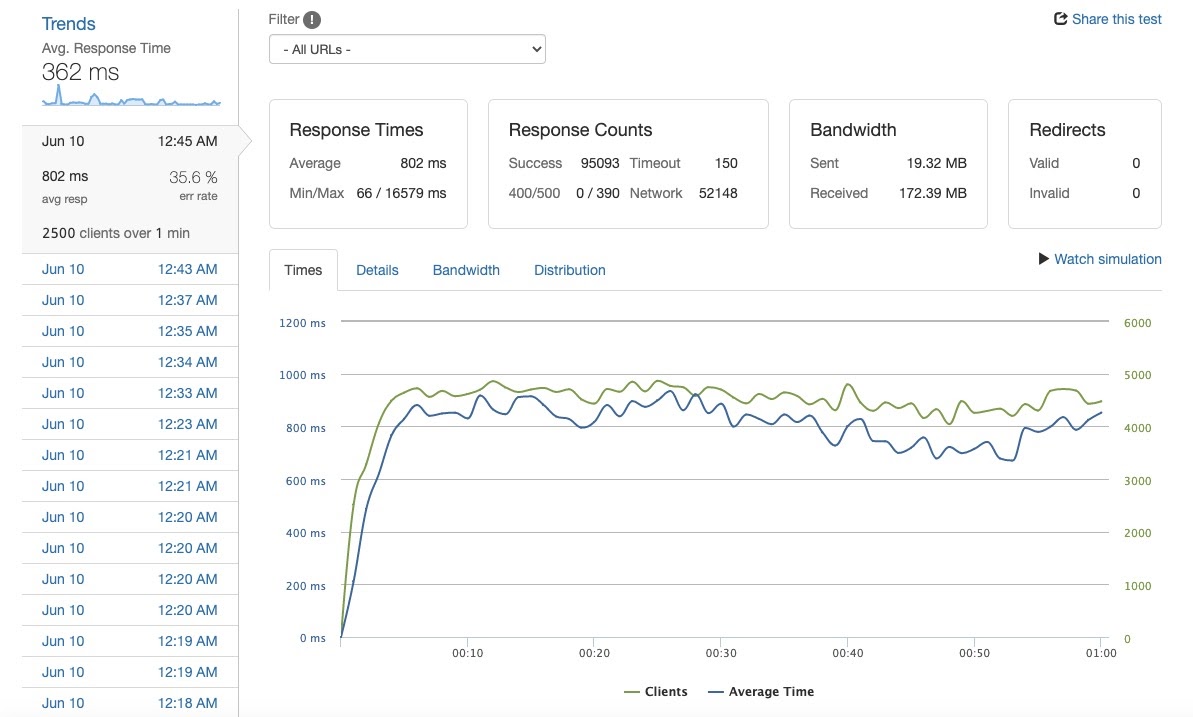

2500 RPS at server 5:

As depicted above, performance rates were actually worse with five servers. External factors or not, it was time to employ new strategies. The NGINX documentation mentioned two possible options for load balancing. The default was "round-robin", where requests would be sent to each server following the same order. There was also the option of "least-conn", where requests would be sent to the server most available to handle a new request. We tried that out:

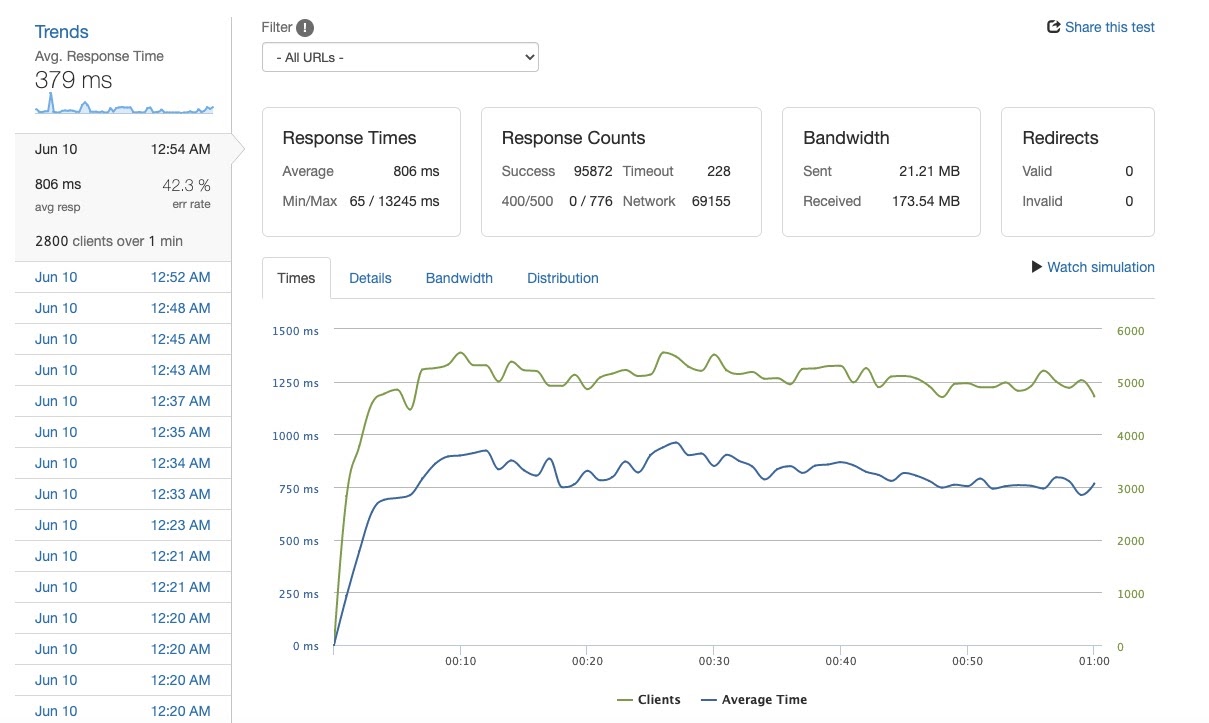

2800 RPS round-robin:

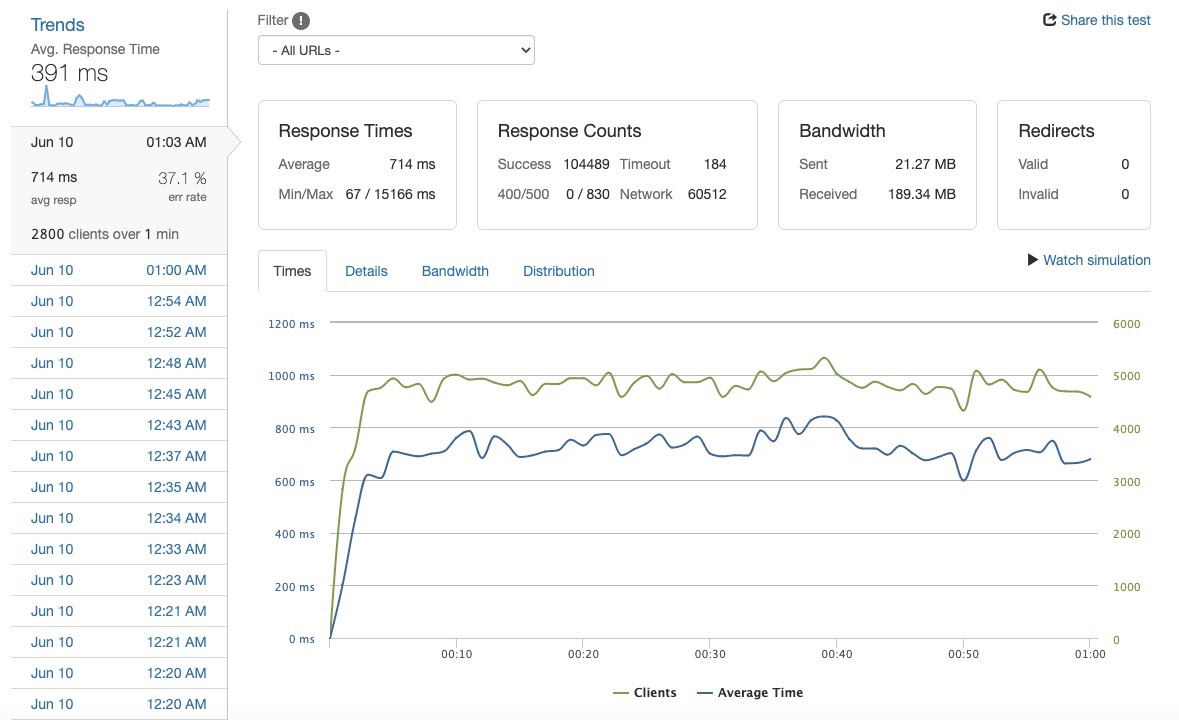

2800 RPS least-conn:

As pictured, we achieved a dip in latency and error rate when after switching over to least-conn. Not bad!

Caching

Another optimization tweak NGINX offered was data caching. The idea of caching is that data gets stored in an accessible location, such that next time the data is called for the server needs not reach all the way into the database to acquire it.

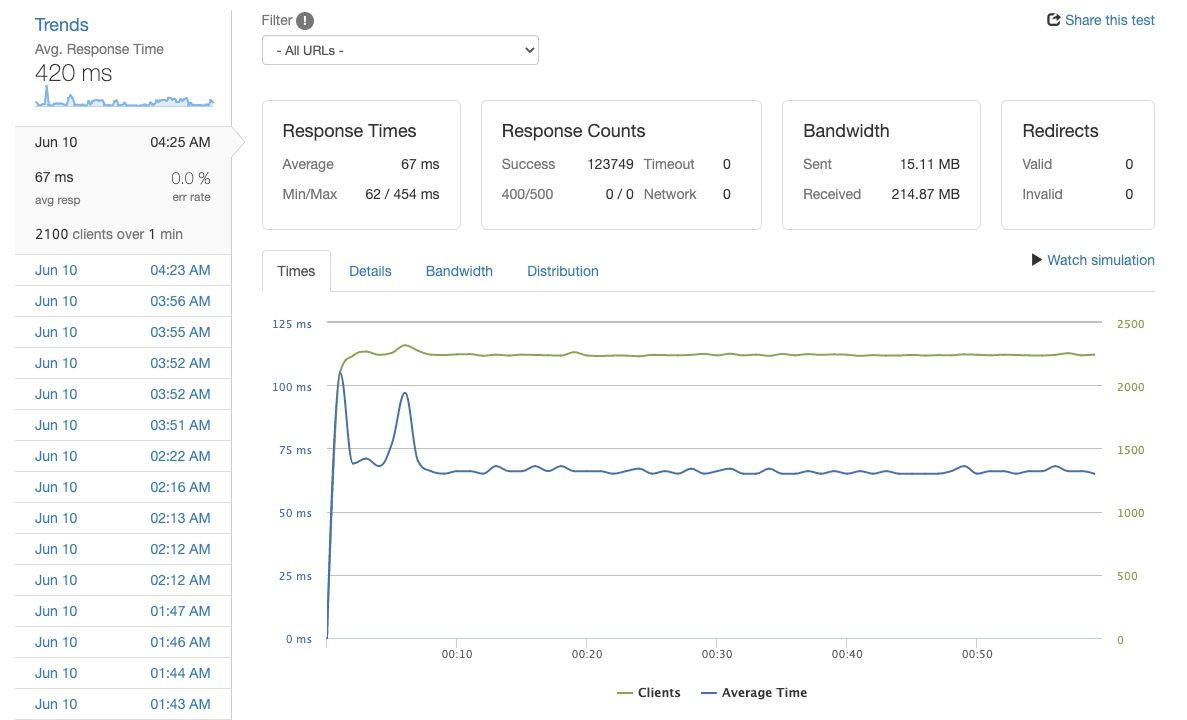

Notice the least_conn and caching directives. With this in play, we ran our Loader.io again.

After multiple tests, I arrived at the highest RPS with 0% error rate.

I was able to handle 2100 RPS with 67 ms latency. It took 4 load balancers, least_conn, and caching to achieve this result. Compared to 80 ms latency at 500 RPS, I would say the experimenting has led to a success.

Reflection

At the end of the day, my team and I learned a lot about what it takes for a production level site to handle traffic. We were exposed to the limitations of certain strategies and realized that tradeoffs were required when it came to optimizing a server. As it holds true for most cases in programming, there’s no one-size-fits-all method for server improvement. Overall, the main take away would be to keep benchmarking and testing new strategies to further optimize results. I hope you enjoyed following me on this journey and gained some knowledge or even inspiration from it. Remember, stay focused and always stay learning!

Further Readings

Designing a Custom Logger Tool | 5 min

Considerations and functionalities of the custom internal logging tool for HealthSafe ID. Featuring some nuances of TypeScript enums and JavaScript symbols.

Credit Card and Payment Management | 8 min

An overview of my journey implementing multiple payment processing methods for Duffl.